|

|

|

Recent Press Coverage

|

| |

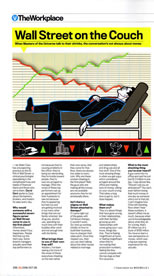

Back in the seventies, when people marched into the world with convictions about changing it, burnout was considered a noble affliction. It meant that you’d depleted yourself while helping others. Almost all the research that’d been done on the subject, and there’d been quite a lot, was on the people in the “caring professions”—nurses, public-school teachers, legal-aid workers, social workers, clergy. Because many of these people were idealists, and because they worked with the hardest-luck cases, they were highly susceptible to disillusionment. Those who burned out were not only physically and mentally exhausted; they were cynical, detached, convinced their efforts were worthless. They held themselves in contempt. Worse, they held their clients in contempt. They began to loathe the same people they originally sought to help. In her seminal book Burnout: The Cost of Caring, Christina Maslach, perhaps the best-known burnout researcher working in the United States today, collected plenty of vivid, unvarnished testimony. As one Florida social worker told her, “I recently received a call at night, and while I was getting dressed, I was screaming and cursing these motherfuckers for calling me with their goddamned problems.”

Today, in New York City, everyone knows that the ones “screaming and cursing these motherfuckers for calling me with their goddamned problems” are as likely to be hedge-fund managers as any species of do-gooders. Burnout is the illness of just about any averagely driven, obsessive New York professional. Bankers, high-tech workers, advertisers, management consultants, lawyers working in their mustard-lit honeycombed Hades—all of them are as likely to complain about burnout as schoolteachers and social workers. In 21st-century New York, the 60-hour week is considered normal. In some professions, it’s a status symbol. But burnout, for the most part, is considered a sign of weakness, a career killer.

“My clients are perfectionists,” says Alden Cass, a therapist to both corporate attorneys and men on Wall Street. He’s young, about the age of a hungry broker, and he looks like the men he treats—strong features, dark teased hair, Turnbull & Asser striped shirt, nice watch. “They have very rigid ideals in terms of win-lose,” he continues. “Their expectations of success are through the roof, and when their reality doesn’t match up with their expectations, it leads to burnout—they leave no room for error or failure at all in their formula.”

Cass is the opposite of a rumpled therapist or academic who might have studied burnout in the seventies. He’s today’s version, a $350-an-hour executive coach, someone who accommodates busy schedules by meeting over lunch or at baseball games and speaks in the idiom of Wall Street. His clients, too, are the inside-out version of the burned-out altruists people were examining in the seventies: Unblushingly ambitious, rich, focused as Marines. Yet ask Cass why his clients are burning out, and his answer isn’t any different for a banker than it would be for a public-school teacher; there’s a gulf between what they expected from their jobs and what they got. “I can’t tell you,” he says, “how many people come into my office and ask, ‘How come I have this money and I can’t find happiness?’ ”

So what does he tell them? “That happiness equals reality divided by expectations.”

I look around Cass’s office and realize it’s the perfect hybrid of a shrink’s suite and a bond trader’s bachelor pad: a seascape of black leather, that mysterious favorite fabric of rich young men, on the one hand; a menagerie of curios, totems, and exotica on the other. (Though maybe there’s a slight bias toward the bachelor pad—further inspection reveals a Wall Street movie poster in the corner, a bronze bull on the coffee table, and a squishy stress-ball he encourages his stymied clients to throw.)

Alden Cass is sitting in his office, showing me his various tools for reigniting burned-out clients. “I created this thing, bullish-versus-bearish thinking,” he says. He hands me a worksheet with silhouettes of bulls and bears. “I give them for homework so they can monitor their thoughts,” he continues. “Usually, when you’re burnt out, your first thought is vicious, irrational. What we call bearish. So they start monitoring what goes on in their heads. And once they have evidence, they can redirect those thoughts. They have ammo now.”

Because Cass is an executive coach, it’s his job to tell people how to assume responsibility for their own distress. Some contend that burnout says more about the employer than it does about the employee. “Imagine investigating the personality of cucumbers to discover why they had turned into sour pickles,” Maslach famously wrote in 1982, “without analyzing the vinegar barrels in which they’d been submerged!” The trouble is that corporate America has always been leery of the presence of burnout researchers. When Cass tried writing his dissertation about Wall Street burnout, he was turned away from every human-resources office downtown.

The worst case of Wall Street burnout I know is of this guy who wound up driving a cab,” Cass tells me.

A cab?

He shrugs. “There’s a control factor in driving a cab. You go from point A to point B. On Wall Street, you start your day with no idea how it’s going to end.”

driving a taxi doesn’t sound like a particularly soothing solution to burnout. But there’s something to the idea of changing jobs. Maybe extreme burnout victims don’t need a life coach or a sabbatical or a no-meetings week. Maybe what they need is a headhunter.

|

| |

How Wall Street can wreck your life

Those who are successful on Wall Street and Main Street -- indeed in any high-stress job -- are often the most susceptible to depression and self-sabotage.

By Jeanne Sahadi, CNNMoney.com senior writer

NEW YORK (CNNMoney.com) -- Perfectionistic. Driven. Harshly self-critical. Competitive.

Such are the traits of some very successful brokers, financial advisers and traders, said clinical psychologist Alden Cass, who provides coaching and "lifestyle portfolio management" for Wall Street players who are therapy-averse.

They're also common traits among many successful people in other

high-stress jobs, Cass said.

And they're the very same traits that can take you down.

That's because an unforgiving drive to succeed breeds an unhealthy fear

of not succeeding -- and, ultimately, depression whenever your mojo takes

a coffee break, as it's wont to do from time to time.

"When you set your expectations for only success you set yourself up

for big disappointments," Cass said.

A common refrain he often hears from clients is "I'm making all this

money. How come I'm not happy?"

Here's how:

To hard-driving traders, say, a bad month or two defines their year and

feels like the equivalent of "I failed." But, Cass said, "two bad months

does not make a season."

Of course, that can be tough to see when you're already prone to

feeling like a failure if you don't hit a home run every time and you work

in an environment that's all about the bottom line and where you're only

as good as your last at bat. (And, let's be honest, these pressures are

hardly exclusive to Wall Street jobs.)

Among brokers and traders, Cass has seen depression about their

performance turn into a desire to hide from clients and throw themselves

into busy work to turn their minds off. That, of course, doesn't do much

for their numbers, haunting them with thoughts that things will never

change.

"If left unchecked, their emotions can destroy their careers," Cass

said.

That's because negative emotions can fuel some destructive habits.

His clients are most often referred to him by their wives and branch

managers after they've noticed serious changes in behavior: screaming,

being overly demanding of coworkers, harassing women, driving clients to

issue complaints and being what Cass calls "Ice Men" -- emotionally absent

from family and friends. Their marriages become another mountain they have

to move; their wives another person to answer to.

Reliance on Adderall (prescribed to treat attention-deficit

hyperactivity disorder), on sleeping pills and especially on alcohol isn't

unusual. Some of Cass's clients, he said, drink the equivalent of a bottle

of wine a day. Those in their 20s and 30s are more likely to binge

drink.

Potential signs of alcohol dependency (again, not limited to Wall

Street) include having three or more drinks a day, having problems caused

or exacerbated by alcohol and drinking when you know it's dangerous.

Another sign: drinking every night but feeling it's not a problem

because you're still making money and doing well, Cass said.

If you work in a job where every month is a fight to win, "you need

people to hold you accountable for not falling too far off the track,"

Cass said. That is, someone like a boss, partner or friend, who can give

you a little perspective on your performance beyond the last five minutes

and who can remind you what's ultimately important.

In an analysis of the kind of healthy psychology that can help someone

sustain top performance throughout a career, Competitive Streak Consulting --

Cass's company -- highlights a few key traits: a willingness to seek help

when you need it, to view mistakes as opportunities to learn what doesn't

work and to recognize that having a balanced life helps prevent stagnation

and burnout.

Maybe a good first step might be leaving on time tonight ... without

the BlackBerry.

|

| |

Alden Cass has a burgeoning practice as the Dr. Phil of Wall Street - a clinical psychologist specializing in the complicated lives and needs of financial titans and those who serve them. David Dent spoke to Cass about the bankers, brokers and traders he sees every day.

Why would someone with a successful seven-figure career on Wall Street come to you in the first place?

Oftentimes, money doesn't buy happiness. People find that out the hard way. Some branch managers actually send their top performers to me because they're causing problems in the office - they're being too demanding, they're hostile toward people, they're way too arrogant to manage. Often the wives of these top performers set up an appointment for their husbands to see me because they're appearing burned-out and are getting involved in too many other things that are not family-oriented, like drug use, alcohol use, spending too much time with their buddies after work and not enough time with the family.

What brings them to you of their own free will?

Adultery. I've been seeing a lot more of the wives of these executives cheating on the men rather than vice versa. And they come for that. Now, there are always two sides to every coin. Why are these women cheating in the first place? Well, they guys who are making all this money are not available anymore; they're not emotionally there.

Isn't there a stigma on Wall Street attached to therapy?

If I came right out of the gates with full-blown therapy, it wouldn't work. So I end up working initially on how to build their business, how to sharpen their sales pitch. Once they respect you, then you can start talking about the other issues related to marriage and relationships and drug use and all that stuff. One of the most amazing things is when you get a guy who's considered arrogant around the office and making tons of money, sitting on your couch crying. That takes a long time to get to, but it does happen.

What makes them cry?

They cry about things that have gone wrong in their relationships with their families growing up and relationships with wives going sour - you know, things like that. They're feeling insignificant at home or feeling insignificant when they're not making their production numbers, feeling like they cannot compete with the top dogs at their firm anymore.

What is the most shocking thing you've ever heard?

A guy came into my office and said he just lost $1.2million in one day. I was almost like, "Should I call you an ambulance?" You can't even fathom losing that much money in one day as someone who's not in that job. I can't imagine how I'd be still standing. Now when I heard these numbers it doesn't affect me as much, because when you're knowledgeable about what they do for a living, that's $1 million out of a book of $100 million. You have to learn a new perspective on money, which was a big eye-opening experience for me, actually.

|

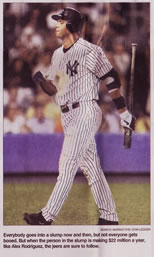

"This game is funny," says New York Yankees starter Randy Johnson. Great players make it look easy, but when they fail, he says, people wonder what's wrong and "sometimes, things spiral."

Former professional tennis player Patrick McEnroe, "In an individual sport like tennis, it's very hard to break out of a slump because it's all about confidence."

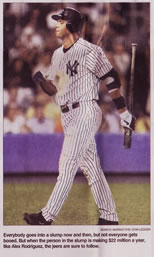

Everybody goes into a slump now and then, but not everyone gets booed. But when the person in the slump is making $22 million a year, like Alex Rodriguez, the jeers are sure to follow.

|

|

When we slump, we're only human. A-Rod? He's a bum

New Jersey Star Ledger

Greg Saitz

Alex Rodriguez, meet Otto Crombet. Rodriguez plays baseball for the New York Yankees, pulls down about $22 million a year and is getting lots of grief lately because he hasn't been able to hit a little round ball.

Crombet sells cars for Montclair Acura in Verona, makes about $22 million less than Rodriguez and has gone through his own ruts moving cars. So he doesn't have much sympathy for the guy they call A-Rod.

"I've come through many slumps and I don't make a pittance of what he makes," said Crombet, a 61-year-old Vietnam veteran who said he pulled through a tough patch of his own this past winter. "Every salesman hits a slump. It's part of the business. Life is not just roses and wine. It's up and down. We all face it, and the successful ones overcome it."

Slumps aren't just for athletes. But you notice the dry spells more when the slumper is someone who makes more in one week than most of us do in a decade.

And in the case of Rodriguez, who has seven times as many strikeouts (14) as hits (two) in his past five games, a slump is enough get him booed every time he walks to the plate. In his home stadium.

Imagine being jeered every time you write a bad story (not that that ever happens). Fail to sell a Sub Zero refrigerator. Or make a bad trade on Wall Street.

"They almost develop a sense of learned helplessness," said New York psychologist Alden Cass, who counsels top producing stockbrokers. "These slumps are normal and cyclical, just like the markets."

Cass, who is president of Competitive Streak Consulting, said he tells the financial advisers and hedge fund traders whom he deals with not to worry about losing a ton of money over the course of a day or a month. He uses a stress ball in the shape of a baseball and tells his clients, "Don't aim, just throw the ball."

Athletes will tell you the same thing, but in interviews yesterday most said they still have their methods for dealing with slumps.

"I probably did a lot of things differently to try to get out of it -- probably a lot of things I shouldn't have done," said Don Mattingly, the Yankees' hitting instructor. "I wasn't the kind of guy who just said, 'I'm going to come out of it.' I would hit more, work more, study more. I changed stances way too much, moved my hands up and down on the bat ... everything.

"Stupid, really, when I looked back on it."

Pro tennis player Vince Spadea was in one of the sport's worst slumps in 2000 -- he had managed to lose 21 straight matches. Performance psychologist John Murray, who worked with Spadea to get him back on track, said oftentimes the harder someone tries (are you reading this, A-Rod?), the worse they do.

"That's because you do things that are not necessary, you overdo it and that leads to a variety of problems," said Murray, whose practice is in Palm Beach, Fla. The key -- for athletes and everybody -- is not thinking about the outcome. "It distracts you from what's relevant, and can create fear and pressure.

"The way to get out of it is to often simplify, back to what I call the beginner's mind."

After claiming, "my whole career was a slump," former professional tennis player Patrick McEnroe said he also tried to visualize a good serve or a good stroke and build on that.

"In an individual sport like tennis, it's very hard to break out of a slump because it's all about confidence," McEnroe said. "When you're in a slump, the other players can sense it in the locker room and they use it to their advantage and it gives them an edge."

Rodriguez, who came to the Yankees before the 2004 season and has been a frequent target of grouchy fans, isn't alone in his struggles. New York Mets third baseman David Wright -- a contender earlier in the season for the National League Most Valuable Player award -- is in the biggest home run drought of his short career.

"This game is funny," said Randy Johnson, the Yankees' pitcher. "I've played and watched a lot of games, and I've played against some of the great players and with great players, and some of them make it look pretty easy. And you know what? It's the day or the couple of weeks that they don't make it look easy anymore, that bad week or couple of weeks or whatever, and we think, 'Oh, what's wrong?' And it's not that easy. Sometimes, things spiral."

In New York, as Johnson and Rodriguez can attest, the pressure to win can only make matters worse.

Mets first baseman Carlos Delgado is playing his first season in New York and hit some rough patches early in the season. He said he has seen players do everything imaginable to turn around their luck, including players showering in full uniform with their bats.

"Sometimes, if it's really bad it can bother you off the field," Delgado said. "But it's not like, 'I didn't get a hit today. I'm going to go home and kill the family.'"

So what's a frustrated Yankee fan to do if A-Rod strikes out five or six more times in today's double-header?

Relax. After all, it's just a game and all slumps run their course.

"The thing about it is once you make a sale, you feel better about yourself and you're apt to make the next sale," said Crombet, the Acura salesman. "If you do the right things -- stay focused -- you very seldom get into a slump."

|

Dr. Cass: ...the industry is now accepting the fact that psychology and business do coexist...

|

|

BROKER-DEALER ROUNDTABLE: Wirehouses face challenges in trying to break product focus

By Dan Jamieson

NEW YORK - The major Wall Street firms face challenges in shifting to a true wealth management consulting role from their traditional focus on product sales, according to a round-table panel of industry consultants.

Some of the wirehouses "are starting now to do a pretty good job of ... taking down all these product silos," said Frank Campanale, chairman and chief executive of Campanale Consulting Group LLC in Birmingham, Mich.

The firms realize that "the real product is the investment strategy [or] wealth management," he said during a round-table discussion that was moderated by the editorial staff of InvestmentNews and which was held at the newspaper's office here Aug. 1.

Mr. Campanale pointed to UBS Financial Services Inc. of New York as one firm that has "started to break these kinds of product barriers down, because it's the way that they've been doing business in Europe for at least the past decade, with this total-investment-solution-type process."

"Just because you're successful as a million-dollar producer in the old paradigm doesn't mean you're going to be successful leading a wealth management practice," said Matthew Oechsli, president of the Oechsli Institute Inc. in Greensboro, N.C. "There's a whole different set of skill sets."

Wirehouses have made some progress in developing programs to develop wealth managers, but the main challenge is continuing training for advisers who want to serve wealthier clients, Mr. Oechsli added.

Many branch managers, for example, aren't equipped to coach their top representatives in forming "a true comprehensive wealth management team," he said.

Firms often turn to outside groups such as the Greenwood Village, Colo. based Investment Management Consultants Association for training, Mr. Campanale said.

But those bursts of training are "like drinking water out of a fire hose," he said. Reps often are overwhelmed and may not implement much of what they learn.

Teaming up

Wall Street brokers must drop their Lone Ranger personae and learn to team up successfully to deliver a higher level of client service, panelists said.

But so far, the results from brokers working in teams have been mixed.

Teaming up has been like throwing "spaghetti against the wall and [seeing] what sticks," said Alden Cass, president of Competitive Streak Consulting Inc. of New York, a psychologist and performance coach.

The challenge for producers has been how to divide work duties effectively, he said.

Mr. Oechsli said that less than 20% of high-level teams function well. Most teams are just piecemeal "work groups," he said.

Both Mr. Oechsli and Dan Sarch, founder of the recruitment firm Leitner Sarch Consultants Ltd. of White Plains N.Y., said they were seeing more teams split up.

Merrill Lynch & Co. Inc. and Smith Barney, the brokerage unit of Citigroup Inc., all of New York, are "leading the charge" in assessing and benchmarking successful wealth management teams, Mr. Oechsli said.

Pressure all around

Brokers at the big firms face pressures from many sides.

First of all, they have to "raise their game" to add value for clients, Mr. Sarch said.

But in the chase for high-value clients, brokers are falling behind their independent competitors.

"The statistics are pretty clear [that the registered investment adviser custodian firms are] capturing about $3 for every $1 the major houses are bringing in in new business today," Mr. Campanale said.

Wirehouse reps can set up their own RIA, "but the mitigating factor has been all these compliance issues," he said. "A lot of them don't want to be a chief compliance officer."

Meanwhile, the wirehouses are pressuring the troops to go upscale. Over the past few years, the major firms have raised minimum account sizes and cut pay on smaller accounts, said Andy Tasnady, founder of Tasnady & Associates LLC of Port Washington, N.Y., a compensation consultant.

And "sometimes big firms have fired a number of people," he said.

A year ago, Morgan Stanley of New York fired about 1,000 of its lowest producers, and it cut about 500 trainees last fall.

Brokers are running into the hard reality that the ultra-wealthy market may not be the best place to grow. Mr. Sarch said he has seen a "trend where brokers are backing away" from this segment, because it is too difficult to break through.

When reps do establish a business relationship with wealthy people, they often get beat up on price, he added.

Meanwhile, compliance burdens are affecting business development.

"What you find is enormous frustration by brokers at all the firms about how the regulations and the procedures bog them down in terms of what they do day to day," Mr. Sarch said.

'War for talent'

Restrictions on how brokers can market themselves, together with competition from independents, have created a "war for talent," Mr. Sarch said.

Good producers who create a quality experience for clients are rare, Mr. Campanale said. Of the biggest firms, "maybe 10% [of brokers] really meet that definition to the extent that I think should be acceptable in the industry today."

Brokerage firms need scale, Mr. Sarch said. That means they always want more brokers.

Yet there is "a tension" between growing head count and keeping a "level of entrepreneurialism and the freedom to let brokers truly do what they want," Mr. Sarch said.

Mr. Tasnady said the preferred approach being followed by the wirehouses is to encourage account growth among top reps.

|

| |

Off the Floor, Onto the Couch

The clients of clinical psychologist Alden Cass are high-flying Wall Street traders. They just need a little help coping with the stress

Since traders have replaced investment bankers and research analysts as Wall Street's rock stars, you might expect them to feel like they're on top of the world. But from where clinical psychologist Alden M. Cass sits in a black leather chair on the 10th floor of a luxury high-rise in midtown Manhattan, that's not the case.

In the last two years, traders who work at hedge funds or trade with banks' capital have inundated his office. Of the so-called proprietary traders at banks, "many suffer from behavioral paralysis," says Cass, who is president and chief consultant at Competitive Streak Consulting. In other words, they're stressed out.

Cass, 30, has built a business out of coaching traders through their anxiety. He starts by trying to make them feel comfortable with him, emulating their wardrobe (power blue-striped shirts, cuff links) and tonsorial preferences (lots of hair gel). The walls of his office are covered with prints of Wassily Kandinsky paintings and a poster from the movie Wall Street.

TRADING SCARED. One of the biggest issues traders wrestle with is a mixed message from their employers. Banks tell them to take big risks -- but not to do anything, you know, risky. Many traders worry that "the people above them are going to come down on them," says Cass. When some make a bad bet, they just freeze, like deer in the headlights.

Consider the case of a trader Cass calls Scared Stiff. After working as a proprietary trader for a few years, Scared had become more afraid of losing money than of not making it. He was trading from a position of fear. Cass advised Scared to stay focused and do his research. Remember, Cass wrote in an e-mail message to Scared, good traders must be willing to risk losing a lot to make a lot. "If you cannot or will not make this investment, you will stress yourself out, pull out of trades prematurely, and bring home peanuts at the end of your trading day."

Cass aims to get through to traders by translating his clinical psychology into trader-speak. For example, he works with them to develop "bullish thinking" even after their trades have failed. He also helps them with "life portfolio management" -- methods to keep traders from behaving like what Cass calls "icemen" at home. "I give them assignments and tasks sometimes, like to take their wives out to dinner," Cass says.

FIRST DATE. But Cass says that most of his work involves making traders face reality when they're overcome by emotions. He talks them through their trading strategies that are not working, and asks them to recall the last time they pulled themselves out of similar ruts. "I ask them if there's any reason they can't do that again this time," Cass says.

Though the questions seem simple, Cass says getting traders to listen to them is not. Many of the best traders like to be in control and don't have many people in their lives who tell them that they're wrong. Plus, most of Cass's clients are sent to him by their wives. As a result, "the first session is always a doozy," Cass says. "Traders size you up and assess if you're any good," Cass says. If you cut it with them, and Cass usually does, "they'll dump their lives on you." And pay you anywhere between $250 and $350 an hour.

|

|

|

Should business execs meet at strip clubs?

...Alden Cass, a Manhattan-based psychologist who works with financial executives, says strip clubs hold a special attraction on Wall Street. He attributes it to the business' highs and lows and tendency to tie people's identities to how much they earn. He says many of his male clients find strippers more understanding than their wives.

"When things are great at work, some of them do feel entitled to have things when they want them," Cass says. "The allure is, 'Someone is going to listen to me on my terms.' "...

|

|

|

Is it time to hire a better broker?

By David Dent

James' professional profile shows no signs of a sucker: He's a 50-year-old entrepreneur who lives in Manhattan's Tribeca neighborhood and runs his own oil-equipment firm. He eats the weak for breakfast. Yet while he regularly jettisons employees who don't measure up, he can't seem to fire his broker - a guy who has racked up tens of thousands in losses.

"He's had a lot of trouble lately; he's going through a divorce," says James, who's taken dinner cruises with his broker and visited the guy's trading floor. James tells his wife, as he tells himself, that he'll ride it out until the broker gets him back to break even. Then he'll scuttle him. They may have a long wait, if you ask Alden Cass, Psy.D., a New York City clinical psychologist known as the Dr. Phil of Wall Street. Cass is a therapist for many leading brokers and he knows all their tricks. He says it's common for brokers to build the bond of friendship with clients because "it's hard to fire a friend."

Firing a broker is just like breaking up with a girlfriend: It'll be a lot easier if you have a new relationship waiting in the wings. But finding the right investment advisor means revisiting some fundamental questions. Do you want high-touch attention from a single advisor or the depth and breadth of an advisory team? Are you looking for somebody who can execute stock trades or provide advice about your entire financial picture? What is your appetite for risk, and how much can you afford to invest?

The choices are daunting...

|

|

|

...Alden Cass, a clinical psychologist and founder of Competitive Streak Consulting, has built a hybrid coaching-and-therapy practice specializing in registered reps. He's not surprised by news reports and lawsuits alleging bawdy, and even offensive, behavior.

"Money, sports and sex drives all these guys," says Cass, who did his graduate school dissertation on depression and Wall Street. Amazingly, the paper was the first of its kind. His findings? Roughly 23 percent of the male population on Wall Street is clinically depressed, as opposed to 7 percent of the general population. But Cass is quick to assert that it's not just Wall Street employees who can slip into anti-social behavior: "I´d say anyone with similar money and power has as likely a chance of crossing those lines." (He mentions former President Clinton as exhibit A.)

It's not just the low-end of the food chain that slips out of bounds, either. He says many of the leading producers he works with, who´ve climbed and clawed their way to the top, can be acutely demanding and controlling, express a sense of entitlement and have difficulty modulating anger. How controlling? Cass says that many of his brokers, when acknowledging past inappropriate behavior, will say, "I don't disagree." It would be more appropriate to cop to the transgression, with a "Yes, I agree" statement. But that´s giving ground, and these people tend to want to stay in control, Cass says.

|

What Makes Alden Run?

|

|

This ambitious young psychologist has staked a claim on Wall Street's psyche. Are brokers ready for their own Dr. Phil?

A day after Dr. Alden Cass was quoted on the first business page of the Sunday New York Times, his Website (www.competitive-streak.com) received 10,000 hits. "I got 9,000 the next day and 8,000 all week from Asia, Europe, South America. And it's continuing today, almost three months later," says Cass, who was interviewed for his Wall Street observations, but not about stocks or bonds.

Instead, this dynamic young clinical psychologist sells his insights on the mental health of Wall Street brokers, traders and investment bankers to the Wall Streeters themselves. For these professionals, Cass says, "mental health is the price they pay for affluence in the good times and for job security in the bad."

As he turns 29 -- yes, 29 -- this month, Cass has been busy giving interviews to publications as disparate as Business Week and Glamour about his latest research report: "Bad Medicine for Wall Street: Alcohol Use Trends During War." Variously known as the "Frazier Crane of Wall Street" or "The Stock Doc" -- after the monthly column he posts on his Website -- Cass has focused his clinical attention on Wall Street much as Margaret Mead focused on Samoa. (On Wall Street was the first publication to bring Dr. Cass' work to light, in an August 2000 story, "Are Transactions Driving You Crazy?")

Having come to know his subjects so well, Cass needed a way to treat a population that appears to thrive on stress, ambiguity and volatility and focuses on a field of activity -- the financial markets -- that themselves mimic characteristics of manic depression.

"The number one distinction between a transactional broker and a casino gambler [is] that the gambler can walk away with his winnings for the day and enjoy it," Cass says. "A broker has to compare his winnings to others around him and can't just walk away from his next transaction."

After receiving his doctorate and going into private practice in New York, Cass' solution was to present himself as an executive coach -- "a kind of go-to person" -- rather than as a therapist. In fact, coaching is an appropriate description since he uses sports metaphors as well as Wall Street argot to relate to clients, most of whose previous experience with therapy has been physical therapy.

"I get [clients] to think bullish thoughts rather than bearish thoughts," he explains. "When they're too discouraged to call clients or make another cold call, I call it behavioral paralysis, not depression. When they need to make a pitch, I say, Don't aim; just throw the ball!'" (If you see someone squeezing a stress ball that looks like a miniature baseball and bears that phrase, you'll know where it came from.)

Cass' goal for most clients is to improve job performance, effectiveness and productivity. "I want to give them a mental edge in terms of beating the tough, bear- market environment," he says.

|

|

|

"Brokers have little control over their jobs or the outcomes of their trades," said Alden M. Cass, a licensed clinical psychologist who wrote the study and now coaches Wall Street traders and brokers on coping with the psychological travails of their professions. "These frustrations can lead to a form of 'learned helplessness,' or a feeling that you are in a prison with no way out. Such feelings have been linked to levels of clinical depression."

Relatively few brokers and bankers appear to be seeking professional help to cope with the pressure, according to data collected by insurance companies. Experts say many brokers fear that doing so would be seen by their employers as a sign of weakness in a high-testosterone industry like finance. So brokers bottle up their feelings and soldier on - until they crack, health professionals say.

Keeping his clients from pursuing the second option has been Mr. Cass's mission for two years. After completing his study on broker depression, Mr. Cass, 28, built a private practice called the Competitive Streak Consulting where he offers executive coaching sessions - distinct from traditional therapy sessions - to a small but growing number of frazzled brokers and bankers. They have spurned the in-house counseling services offered by their employers, choosing instead to pay $250 an hour for coaching from Mr. Cass, who earned his doctorate at Nova Southeastern University in Fort Lauderdale, Fla. Other professionals counsel brokers, but few market themselves as aggressively as Mr. Cass, who has a Web site with testimonials from the bankers he has helped.

With a management consultant's style and his deep summer tan, Mr. Cass does not come across as the typical psychologist. He also brings a knowledge of banking and finance, honed while hanging out in Wall Street bars when he was studying for his doctorate in the late 1990's.

He offers his clients a variety of options so that they may be more productive at the office: straight-up coaching sessions, 24-hour phone access and a special program, called "back in 45," in which he meets a client for a 45-minute lunch and strives to lift him up from the slough of his despond. (Lunch is on the client.)

He takes special care, as well, to talk the language of Wall Street, spurning clinical terms - including the word "depression" itself - that may conjure up in wary brokers' minds the specter of a couch and a ticking clock. Instead, he prefers a more accessible vernacular, encouraging clients to "think bullish," "don't be bearish" and "don't aim, just throw the ball."

|

How trading "shrinks" help the bottom line - It's not just SAC and BAM turning to psychologists

|

|

Cass, the subject of personality profiles in the New York Times and the magazine On Wall Street, takes a similar approach. "The hedge fund traders I work with tend to have more specific problems," Cass says. "It tends to be that they have a lot of trouble seeing their way through a trading slump. It’s like being in a batting slump in baseball – you just keep pressing and pressing – and this is a very elite and competitive work environment. You have pressure from above to produce, and pressure to perform, because a lot of them are perfectionists themselves."

Cass says his coaching program, as opposed to his full-fledged therapeutic treatments, emphasizes reinforcing the connections between what’s going on in a trader’s life and the performance of his book. "There’s a sense of self-entitlement that traders often have when they’re making money – the Masters of the Universe concept," he says. "When things are bad, they don’t know how to survive."

After a succession of losses, traders are vulnerable to "behavioral paralysis," Cass says. "If two traders are sitting next to each other and both lose a large amount of money at the same time, one can think of it as a temporary setback, but the other could start to think he’s a failure, that he doesn’t know why he made that mistake, that maybe he shouldn’t be in the business, then his risk appetite will be lower on the next trade."

|

Sit up and smell the Colombian

|

|

Ritalin, the drug used to treat children with attention deficit disorder, has come into vogue in Manhattan’s financial services sector, says Dr. Alden Cass. The man sometimes called "Wall Street’s therapist" explains: "it’s not so different from cocaine and it keeps you very focused. There’s a thriving black market."

"If you’re a senior executive at a bank," says Dr. Brenner, "it’s often much cheaper to take you out and fix you up than it it to replace you. If you’re talking about being an in-patient for 28 days, that’s about Ł12,000 ($22,600) – a pretty good deal if someone’s on Ł250,000 a year."

Dr. Cass also believes that business recognizes the effects on the bottom line: "My goal is to do it in a way that’s helpful in terms of company wellness. If I improve ‘employee lifespan’ then that’s a dollars and cents benefit to the business. And I think this message is starting to hit. We’re getting more calls from them."

|

|

|

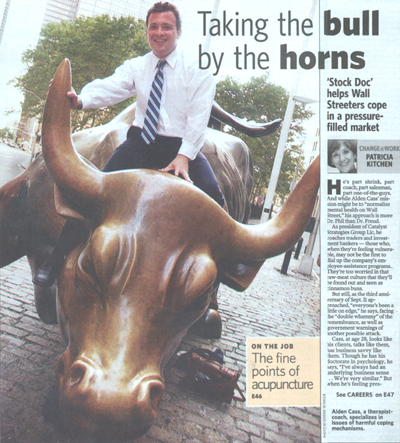

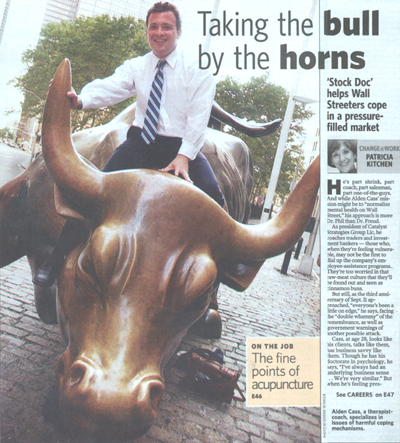

'Stock Doc' helps Wall Streeters cope in a pressure-filled market

Patricia Kitchen

He's part shrink, part coach, part salesman, part one-of-the-guys. And while Alden Cass' mission might be to "normalize mental health on Wall Street," his approach is more Dr. Phil than Dr. Freud.

As president of Competitive Streak Consulting Inc., he coaches traders and investment bankers - those who, when they're feeling vulnerable, may not be the first to dial up the company's employee-assistance programs. They're too worried in that raw-meat culture that they'll be found out and seen as cinnamon buns.

Cass, at age 28, looks like his clients, talks like them, has business savvy like them. Though he has his doctorate in psychology, he says, "I've always had an underlying business sense ... We're very similar." But when he's feeling pressured, he turns to such healthy releases as exercise - instead of drugs, booze and beckoning women.

Just two years in business, he also has a flair for attracting media attention, having been quoted in "The New York Observer" and on Business Week Online, and most recently being contacted by Glamour magazine. Becoming known as the "Stock Doc" thanks to an online column he writes, he's also been cited for research collected from visitors to his Web site, which he and a colleague turned into a report called "Bad Medicine for Wall Street: Alcohol-Use Trends During the War in Iraq," which they presented in poster form in July at the American Psychological Association's convention.

His coaching clients are mostly men in their 20s, 30s or 40s, often looking to improve productivity to better compete in that unforgiving Wall Street environment. He offers office sessions for $250. And for $350, those with emergencies can schedule a "Back in 45" lunch or dinner session and get follow-up phone coaching for the week. He's even conducted a coaching session on a boat ride to Yankee Stadium. And as a licensed therapist with a private practice, he can also address his clients' more deep-seated issues.

Among those he's seen: an investment banker abusing ritalin and cocaine just to get himself through the long days; a trader stuck in "behavioral paralysis" (Cass' code phrase for depression); another trader who started looking to alcohol for solace after his earnings plummeted from $125,000 to $50,000 when he changed jobs. Says his friend Matthew Albano, a lawyer-turned-broker, "Alden's just like the guys he's talking to. He's the same age. He's a single guy." In fact, before he knew him well, Albano heard Cass talking about his work and says, "I thought it was a pick-up line."

"These young kids are closing $30- to $40-million deals by themselves. They're always on. It's tough to turn that off."

So, if we put together his entrepreneurial leanings and media buzz, do we see a reality television show in his future? Certainly, he says, there would be no lack of material. "You couldn't make up the things I hear." But he doubts anyone in the financial industry would want to air them publicly. And besides, all he wants is to be known as "the go-to guy on Wall Street."

Please send e-mail to pkitchen@newsday.com.

|

|

|

|

|

|

'...many of them feel like a lost generation, worried that their peak

earning years are behind them even as their expenses jump. For the youngest,

the costs of raising families and paying mortgages lie ahead. For those

closer to middle age, the burdens are heavier. "These guys are despondent,"

says Alden Cass, President at New York's Competitive Streak Consulting who studies laid-off brokers. He knows ex-Wall Streeters

who are tending bar, waiting tables, or working at the likes of RadioShack

and the Gap.'

|

|

|

|

|

|

Cass stated "The unwritten rules within these firms is... just donąt talk about it. "

regarding the financial advisors inability to feel comfortable talking about their painful feelings in the context of the work environment.

|

|

|

|

|

|

“It’s amazing to think how much

suffering there is right now, but the

symptoms of major depression existed

well before September 11” said

Alden Cass. [Dr.] Cass believes his

findings should interest not only

stockbrokers but all concerned about

the health of the market. Retail brokers,

after all, play a key role in

attracting the new money that helps

push up share prices. When they feel

down, the volume sales calls they make

to potential investors can fall by as

much as half....

|

|

|

|

|

|

Brokers may be more vulnerable to

clinical depression than the rest of

us. “A lot of these guys have manic-depressive

tendencies that are

triggered by the volatility of the

market. They also lack the insight or

the coping skills to deal with the

stresses of the market,” said Cass.

“As a result, it’s natural to find higher

levels of depression amongst them.”

There’s a reason your stockbroker’s

not taking your calls: His pain is

greater than yours.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Researchers Alden Cass, et al of Nova’s

Center for Psychological Studies

interviewed 26 male stockbrokers ...

chosen from seven of Wall Street’s

most prestigious firms. Twenty - three

percent met the criteria for clinical

diagnosis of major depression, roughly

three times the national average for

males reported by the National

Institute of Mental Health.

Despite these signs these individuals

were performing well per year.

...Brokers who showed the greatest

signs of depression, anxiety, emotional

exhaustion and poor coping skills were

also the most successful financially. “In

essence, these rookie brokers appear to

be paying for financial success with

their mental health and their quality

of life,” Ultimately, they believe the

stress experienced by these brokers

leads to burnout, absenteeism, and a

loss of productivity, all of which can

be costly for their employers. “You

can’t change the stock market,” says

Cass, “but the study does point to

the need for Wall Street firms to

include stress-management as part of

their training programs.”

|

|

|

|

|

|

Bullion market on the couch: a psychological assessment

Description: The patient, named Mr. Goldfinger for the purpose of this presentation, is a 5,000-plus-year-old commodity residing within the precious metals sector and in use all over the world... Let us now examine Mr. Goldfinger using a medical-model, case-conceptualization format, and try to ascertain whether or not the various external forces in his upbringing have elicited within him a sense of inferiority and/or helplessness, both of which are symptoms that may precipitate a diagnosis of Major Depressive Disorder.

Treatment:

- Industry must recruit younger generations through marketing and active solicitation.

- Central banks should view gold as an effective barometer of inflation to maintain its utility.

- View gold traders as mature business participants who have a specialization.

- Beware of irrational exuberance... Trading based on emotion is the surest

path to failure.

If gold is going to move dramatically, the dollar is going to have to weaken. This has already started occurring, and the events since Sept. 11 may have served as the Prozac for gold in motivating it to some activity.

Dr. Alden Cass

President

Competitive Streak Consulting

|

|

|

|

|

|

As Portfolios Shrink, Retirees Warily Seek Work

They're apprehensive about having to compete for positions with younger workers who may be more technologically advanced.

Dr. Michael Nuccitelli

Managing Director

Competitive Streak Consulting

|

|

|

|

|

|

Broker Burn-out

“They have a perfectionist personality style that makes them incapable of enjoying success for more than 30 seconds before they need to compete against the top dogs of their firms. The whole industry is based on how much money they’re bringing in,” says Alden Cass, who conducted the study as a clinical psychology doctoral candidate and is now President of Competitive Streak Consulting, in New York City. Offering unique forms of treatment, the company’s goal is to “normalize mental health” in the business sector. It is zeroing in on financial advisors in particular.

“There’s a stigma attached to mental health within the business,” say Dr. Cass, who is conducting a survey of alcohol and drug use (see www.competitive-streak.com) to determine “how many people are self-destructing and to help them realize it before it’s too late.” “The whole credo is, ‘if you can’t take the heat, get out of the kitchen.’ Most individuals never use Employee Assistance Programs because they’re afraid the company will find out about it. It’s almost paranoia.

“But if they’re having problems, they won’t perform at a level to keep them effective enough to be a top [producer]. So it behooves them to use these programs,” says Cass, “and not believe it’s a conspiracy that will cause them to lose their jobs.”

Alden Cass, whose Competitive Streak Consulting offers private coaching without record keeping and substance-abuse treatment that centers around “thinking your way out of a situation,” helps advisors deal with “negative and counter-productive interpretations.”

He says, “If you believe that a stock [falling] is your fault and you don’t take into account the likelihood that it has something to do with what’s out of your control, then you’re keeping yourself down a lot longer than you need to be. That’s going to hamper your ability to pick up the phone and call your next possible investor.”

Dr. Alden Cass

President

Competitive Streak Consulting

|

|

|

|

|

|

One 20-year transactional broker in New York City, suffering from “behavioral paralysis,” sought Cass’ help. “Hiding from clients is a symptom of wanting to stop taking [our share of ] responsibility for the [market] losses. If I can’t pick up the phone to make a presentation, that’s a negative reaction.

“I felt burnt out,” he says. “The bear market has been tough in every way. Now I’ve learned to take a different mental approach and reassess things from a more logical perspective and not react emotionally. I’m being proactive, recognizing what has to be done and doing it.”

- from Research Magazine article “Broker Burn-out”

Dr. Alden Cass

President

Competitive Streak Consulting

|

|

|

|

|

|

Elite Retreat Buyouts

Dr. Alden Cass, clinical psychologist and President of Competitive Streak Consulting, Inc., in New York, NY, agrees that isolated retreats are very good for employee relations, employee performance, and employee mental health — and ultimately for job satisfaction which relates to turnover rates and overall company performance in the marketplace. “In corporate America, everything is very competitive... and people are under a lot of stress on a daily basis from minute to minute,” he says. “Under this kind of pressure, people stop being people in those moments. They become very depersonalized.”

Depersonalization, he notes, is one of the three components of job burnout.

“Depersonalization is a defense mechanism implemented against painful affect or painful emotions such as stress, anger, and frustration,” says Cass. “People become more cold and callous toward others in their immediate work environment and less sensitive to other people’s needs. By taking employees out of the work environment and putting them into a ranch or resort with the same co-workers they are used to seeing everyday at work, the group will develop some cohesion. People begin to realize they are actually a support network for each other rather than adversarial competitors for their jobs.”

“A resort or retreat takes employees out of a stressful work environment and helps them better appreciate the people they work with normally in a different way and under different conditions. They come back feeling like they’re a closer part of a team,” explains Cass.

“Off-site retreats often occur without the actual manager there — and employees are not under pressure when the person who can fire you isn’t there judging you. That means the attendees can relax a little and not worry about being hyper-vigilant,” he adds. “Managers should try not to foster an environment that’s overly competitive because that can lead to a great deal of burnout for employees.”

Dr. Alden Cass

President

Competitive Streak Consulting

|

|

|

|

|